Utility Tree in Software Architecture

Overview

Ever found yourself drowning in a sea of requirements, each one claiming to be “critical” for your software architecture? You’re not alone. In the realm of software architecture, architects rely on significant requirements when making architectural decisions. In my previous post, I summarized the definition and characteristics of Architectural Significant Requirements (ASRs). These requirements demand careful consideration during design, not just because they’re challenging to implement, but because ignoring them can lead to costly rework down the road.

But here’s the catch: when you’re staring at a long list of ASRs that all seem equally important, finding the optimal solution becomes a puzzle. Some requirements might conflict with others, while some might demand significant effort for minimal business value. This is where Utility Trees come into play—a technique that helps you cut through the noise, reduce the number of requirements to a manageable set, and prioritize them based on what truly matters.

Utility Tree Structure

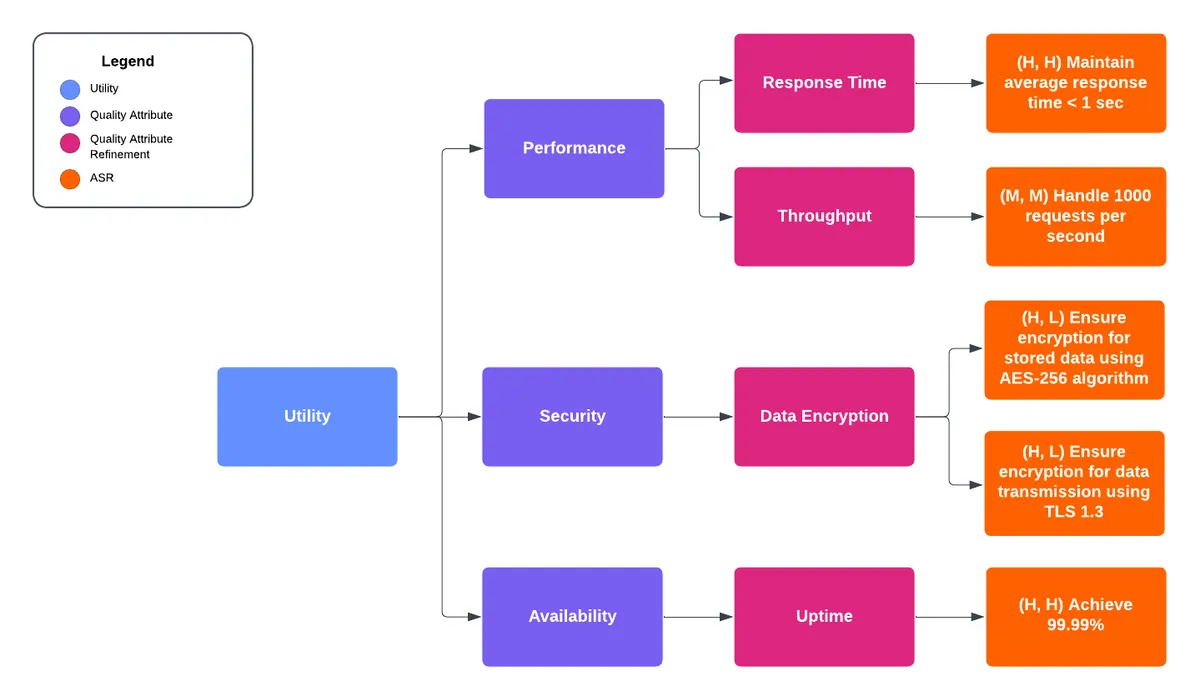

Building a Utility Tree follows a straightforward process:

- Start with the word “Utility” at the root—this represents the overall value of your system.

- Branch out major quality attributes from the root (think Performance, Security, Availability, and the like).

- Drill down by specifying refinements for each quality attribute. For example, under Performance, you might have “Response Time” or “Throughput.”

- Add corresponding ASRs under each refinement, expressed as quality attribute scenarios that are specific and measurable.

- Evaluate each ASR based on two dimensions: Business Value and Architectural Impact, using H (high), M (medium), and L (low) labels.

While Utility Trees are traditionally visualized as tree diagrams—which beautifully illustrate the hierarchical structure—I’ve discovered that a table format often works better in practice. Tables make the information easier to scan, reference, and share with stakeholders who might not be as visually oriented. Plus, they’re much easier to maintain as your requirements evolve.

| # | Quality Attribute | Refinement | ASR | Business Value | Architectural Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Performance | Response Time | Maintain average response time < 1 sec | H | H |

| 2 | Performance | Throughput | Handle 1000 requests per second | M | H |

| 3 | Security | Data Encryption | Ensure encryption for stored data using AES-256 algorithm | H | L |

| 4 | Security | Data Encryption | Ensure encryption for data transmission using TLS 1.3 | H | L |

| 5 | Availability | Uptime | Achieve 99.99% | H | M |

Architecture Impact Estimations

Before you dive into collaborative sessions with stakeholders, there’s some homework to do. This preparatory work sets the stage for productive discussions and ensures you’re not flying blind when the real conversations begin.

The exercise involves two key steps:

- Build your Utility Tree and record all the ASRs you’ve identified.

- Estimate the Architectural Impact of each ASR, categorizing them as High, Medium, or Low.

What does “Architectural Impact” actually mean? A high impact ASR is one that significantly shapes your architecture—think decisions that ripple through your system design, influence technology choices, or require substantial architectural patterns. A low impact ASR, on the other hand, might be important but doesn’t fundamentally alter your architectural approach.

By completing this exercise, you’ll walk into stakeholder sessions with a clear picture of which requirements will really move the architectural needle. This knowledge becomes your foundation for meaningful discussions.

One crucial note: resist the temptation to guess Business Impact at this stage. Leave that column empty. Business value isn’t your call to make—that’s what the stakeholders are for.

Business Value Estimations

Now comes the collaborative part. Organize a session with your stakeholders to review the ASR list, engage in meaningful discussions, and get their perspective on Business Impact. This is where the rubber meets the road—where technical requirements meet business reality.

During these sessions, guide the conversation with probing questions. Ask things like: “What happens if we don’t implement this ASR?” or “How does this requirement translate into actual business value?” These discussions often reveal surprising insights. You might discover that what you thought was critical is actually nice-to-have, or that a seemingly minor requirement has significant business implications.

The goal is to have stakeholders assess and estimate the Business Impact for each ASR using the same H (High), M (Medium), and L (Low) notation. This creates a common language and ensures everyone is aligned on what truly matters.

Working with the Utility Tree

Once you’ve populated your Utility Tree with both Architectural Impact and Business Value, patterns start to emerge. ASRs labeled as (H, H)—high business value and high architectural impact—are your golden requirements. These are the ones that deserve your full attention.

But here’s a reality check: if you find yourself with too many (H, H) requirements, you might be setting yourself up for failure. Building a system that perfectly addresses every high-impact requirement is often unrealistic, not to mention expensive. As an architect, your goal should be to reduce the number of ASRs with high architectural impact: (H, H), (M, H), and (L, H).

The secret weapon here is refinement. Take a requirement like “Availability: the application should be available 24/7.” Architecturally, achieving 100% availability is incredibly challenging—it requires redundant systems, failover mechanisms, and significant complexity. But do you actually need 100%? For most websites, 99.9% availability (roughly 8.76 hours of downtime per year) is perfectly acceptable and much more achievable.

By critically evaluating each ASR and refining them to match actual business needs rather than aspirational goals, you can strike a balance between architectural feasibility and business requirements. The result? A realistic set of ASRs that guides your architecture without setting you up for an impossible mission.

Making Informed Architectural Decisions

With your prioritized Utility Tree in hand, you’re now equipped to make informed architectural decisions with confidence. This prioritized list becomes your north star, guiding you through the complex landscape of architectural choices.

The most important ASRs—those with high business value and high architectural impact—serve as your primary decision drivers. When you’re evaluating architectural patterns, technology choices, or design approaches, reference these ASRs to build strong, defensible arguments. Every significant architectural decision should be traceable back to your Utility Tree, with clear justifications for why a particular choice best serves your prioritized requirements.

This isn’t about making perfect decisions—it’s about making informed ones. Instead of relying on gut feelings or hoping things work out, you’re building your architecture on a foundation of prioritized, validated requirements. That’s the difference between architecture by accident and architecture by design.

Key Takeaways

-

Utility Trees transform chaos into clarity by organizing ASRs into a structured, prioritized framework that balances business value with architectural impact.

-

The two-phase approach works—architects assess architectural impact first, then collaborate with stakeholders to determine business value. This separation prevents bias and ensures both perspectives are properly considered.

-

Refinement is your friend. Don’t accept requirements at face value. Question whether “24/7 availability” really means 100% uptime or if 99.9% would suffice. Realistic requirements lead to achievable architectures.

-

Prioritization enables trade-offs. When you understand which ASRs truly matter, you can make informed decisions about where to invest your architectural complexity budget.

-

Traceability builds confidence. Every architectural decision should connect back to your Utility Tree. If you can’t explain why a choice serves your prioritized ASRs, it might be time to reconsider.

The Utility Tree technique doesn’t eliminate the complexity of software architecture, but it does give you a systematic way to navigate it. By focusing on what truly matters—both to the business and to the architecture—you can build systems that are both technically sound and strategically aligned.

Further Reading

Have you used Utility Trees in your architecture work? I’d love to hear about your experiences and any challenges you’ve faced. Reach out on LinkedIn or share this article with your network if you found it helpful.